STOPPING MASS SHOOTINGS (Part 2)

by Brendan Steidle

Understanding Public Shootings

Mass public shootings are terrifying. I think about them from time to time, in a public space, standing in a crowd or shunted into a corner, waiting for an elevator or sitting in a stadium. You can't help but think about them—because we've all read the headlines. We've all seen the pictures and in some cases, the grainy video. The footage of a blurry figure stalking through the frame, gun in hand.

Mass public shootings are why we have debates on guns today. We're not talking about gun control because we're trying to prevent bank robberies or muggings or home invasions or bar-room brawls. We're talking about gun control because of Columbine and Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook and San Bernardino and Uvalde. We're talking about gun control because of what happened at the Pulse Nightclub. And what's bound to happen next week, next month, next year—that will turn a place name into a chilling reminder of inhumanity.

But...but what if we could stop it?

That's what the gun control argument is all about—stopping gun violence like mass-shootings. Advocates say: let's make it harder for killers to collect assault weapons, harder for those with domestic violence records to get their hands on handguns, harder for those with criminal records to arm themselves with more weapons to commit more crimes.

But gun control has stalled—and though any measure that reduces the availability of guns is likely to in some way reduce the risk of gun violence, assault rifle bans and magazine size restrictions and universal background checks are unlikely to be passed anytime soon. And even if they did pass, that passage probably won't stop mass shooters in their tracks.

But that can't be the end of the road. We have to think harder—think smarter—think about more ways we can reduce gun violence—this most terrifying form of gun violence, mass public shootings, without the need to get 60 votes in the Senate. Without a veto-proof majority, without going head-to-head with the NRA. Let's think of some things we can do without legislation to stop mass public shootings. And let’s start now.

First—what is a mass public shooting?

The definition is exact: A shooting that happens in public that kills four or more people.

Public is pretty clear—it can't happen at home.

It's the four or more that I'm getting hung up on here. I mean—I know we can't call every murder a mass public shooting. One person hardly makes a "mass"—but there have to be mass public shootings that kill fewer than four and are still terrifying, right?

By this definition—the four or more definition—if someone goes on a rampage with a rifle and shoots 18 people—but nobody dies, it’s not considered a mass shooting. So the July 2012 shooting at the Copper Top Bar in Tuscaloosa, Alabama—where someone went on a rampage with a rifle, shot 18 people, but nobody died—that event isn’t technically a mass public shooting. By the four or more definition, if someone takes a handgun and an assault rifle to work, shoots people, wounding 14 but ultimately killing only 3—as in a February 2016 incident at a lawn care manufacturing plant in Newton, Kansas—it’s not considered a mass public shooting.

This is a problem. The four or more definition is a problem if we're trying to get a sense of the size of mass public shootings. So some have tried to modify the definition. To say a mass public shooting is one where 3 or more people are killed, rather than 4 or more. But that wouldn’t include a March 2001 shooting at a high school in Santee California where a student brought a handgun and shot 15 people—killing two. Or one that wounded 8 and killed two at a Portland nightclub in January 2009. Or a shooting at a mall in Columbia, MD in January 2014 that injured 5, killed 2 and included not only a shotgun, but explosives. Or—in total—130 other terrifying shootings over the last 15 years that just don’t make the four or even the three casualty cutoff—but that in total hurt nearly 500 people.

So a three-or-more definition won't work either. Because what we're ultimately afraid of, what we're trying to stop, isn't some statistic calculated after the fact—it’s the terror of someone firing a gun at people in a public place.

That simple definition—happens to be exactly the definition that the FBI tracks. The bureau tracks all public shootings, even if nobody is ultimately killed. They call them: "active shooter incidents.”

This is better because it captures more of what we're afraid of. There are more incidents to track, more to study and try to understand. So let’s take a look. Here are “mass public shootings” (defined as 4 or more people killed) in the 15 years from 2001 to 2016:

This is from FBI’s latest dataset—it tracks everything from December 2000 straight up to the biggest mass public shooting incident in US history: the Pulse Nightclub in the middle of the summer of 2016. That first incident killed 7 people. The last one killed 49.

Let’s dive in:

Now, the FBI provides a 29 page PDF to work with, with each incident in paragraph form. That’s useful as a kind of quick reference, but we’ve gotta get this thing into a spreadsheet so we can run some numbers. So we can get a sense of how these 213 incidents connect.

All right—so it took way more hours than I thought, but I put together a spreadsheet with: 213 rows across 43 columns. That’s over 9,000 little discreet cells of data.

The first thing I noticed:

There are more active shootings now than there used to be. In the first year of the complete data set—the year 2001‚there were 7 active shooter incidents in total. That works out to about one incident every 52 days. In the last 365 days of the dataset—Summer 2015 to Summer 2016—there were 22 active shooter incidents. That’s an average of one incident every 15 days. So rather than reading about an active shooter event in the news roughly every two months, we now read about it roughly every two weeks.

Yes, incidents are increasing—but isn’t each incident also more deadly than it used to be? I mean, the last incident in the data set—the Pulse Nightclub Shooting—was the deadliest in US history, right?

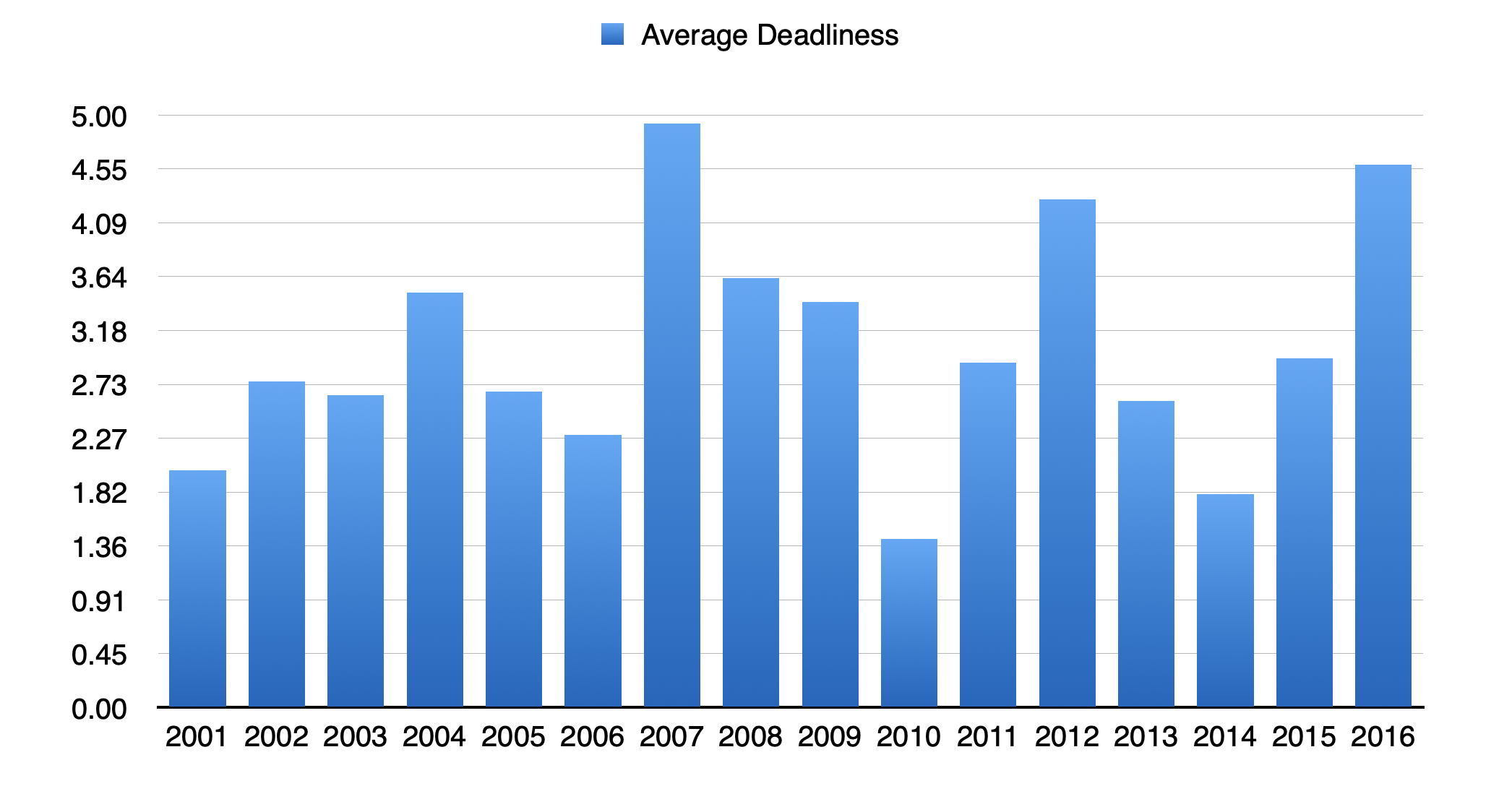

To test this common wisdom, let’s look at the average number of people killed per incident each year. In 2001, there were 12 people killed in total across 6 incidents. So on average, each incident resulted in two deaths. Let’s do that for each year—and we get this:

All right, so the first thing I notice—before we even get to the trend line—is that the average isn’t all that high. The average incident kills between a low of about 1.3 people in 2010 and a high of just under 5 people in 2007. That’s not nearly as high as you might expect.

And here’s that trendline:

So deadliness isn’t really increasing all that much. There is an increase, though. You can see it in the slight slant of that line. That’s really surprising and not at all what I expected to find. Especially with all of the talk about assault weapons and high-capacity rifles. Especially considering that the federal assault weapons ban was in effect for the first four years of the dataset, but not in effect for the last 11. And yet, 2014 was less deadly per incident than the first year in the series, 2001. And even if we did extrapolate out from 2016—the year with the single deadliest incident, 2016 was still less deadly than 2007.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t some really deadly incidents out there. We’ve all read about them. But you can’t say that the average shooting is getting more deadly. It isn’t.

What does the average incident look like, though? Is there even such a thing?

I mean—if someone opens fire in public, what’s the most likely outcome?

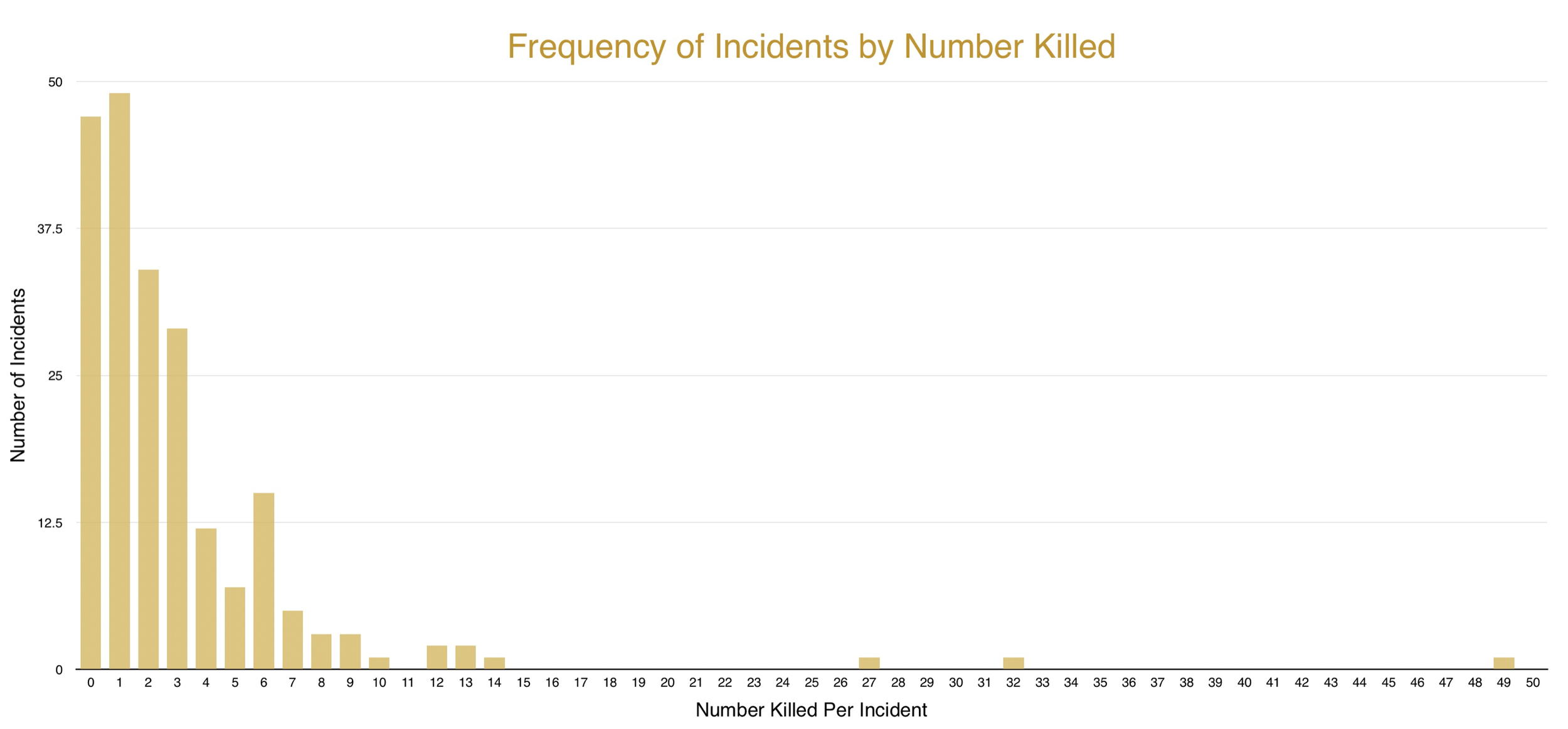

To try to understand this, let’s sort our data by deadliness and add it up. When we do that, we have 47 incidents where literally nobody was killed. And we have 49 where one person was killed. There were 34 incidents where two people were killed, so now we see the number dropping off. Here’s what that looks like:

It drops off really steeply. If someone opens fire in public, the most likely outcome is that just one person is killed. The second most frequent outcome is that no one is killed at all. A graph like this really shows just how crazy those three outliers are—the massive-casualty incidents. The one at 27 is Sandy Hook Elementary. The next one at 32 killed is the Virginia Tech shooting. And the one at 49 is Pulse Nightclub. (Missing from this FBI dataset are events that took place after 2016—including the deadliest US incident in Las Vegas. I address that incident in detail at the end of this chapter.).

Those events stand out in the FBI dataset and they are terrifying—and there’s a lot more to say about those incidents—but they are not the majority. They are not even the average or close to average. This graphic doesn’t look like this:

It doesn’t look like this:

And it doesn’t look like this:

And the number killed graphic isn’t a fluke. We can do the same thing for the number of people who are wounded—and we get the same looking graphic:

What the shape of these two graphs tells us is that active shooter events fall into a recognizable pattern. They’re governed by similar forces wherever and whenever they happen to occur. These forces tend to keep the number killed very low—but not low enough. I’ll address what makes a shooting an outlier later in this chapter. First, let’s look at the stages of a mass public shooting.